Eye of the Storm: the impact of ‘not knowing’ on mental health

Monday May 10, 2021

Retinoblastoma Awareness Week promotes life and sight-saving early diagnosis. Sandra Staffieri, Rb Care Coordinator at the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, highlights the importance of raising awareness among parents, caregivers, health professionals and survivors; and how lack of knowledge and delayed diagnosis can impact children, parents, and adults with second cancer risk.

The quotes used in this blog have been drawn from previous One Rb World meetings, and comments made by parents during my doctoral research.

Turned eye (strabismus).

White pupil (leukocoria).

The First Signs…

The earliest signs of retinoblastoma are a white pupil (leukocoria) or a turned eye (strabismus/squint). The child will likely be otherwise well, and will not demonstrate any outward sign that there is a serious problem needing urgent attention. This peculiarity of apparent wellness contributes to longer lag times from when a sign is noticed to actual diagnosis. These lag times are attributed to parents not knowing the signs are important, and to healthcare providers not recognising parent concerns as significant.

“It is torture to remember how I photoshopped a black pupil on the whiteness in my child’s eye. Oh, dear God how many more years of life she could have had, if we had only known.”

“I threw away so many pictures, thinking there is a problem with the flash. I did not even know cancer can come in the eye. I think I am an educated man, but I did not know how to protect my son by this way. How did I not know this simple thing?”

“It is not an acute situation… I wouldn’t see a turned eye and think ‘Oh, that is an emergency’… It doesn’t seem like an emergency it seems like a developmental problem that you can get addressed in due time.”

“They can look a bit cross-eyed early on and then they grow out of it…do they grow out of it?… you’d hope by toddlers…you’re just hoping that happens.”

Parent stories indicate that seeing the white pupil or turned eye in isolation may not be enough to raise their concern. Perhaps it was only the combination of both signs together that alarmed them enough, prompting a visit to a healthcare professional. It is not widely known that either of these signs could be the clue to a child’s serious eye – or indeed health – problem.

“My wife saw the white first, then my mother. I didn’t believe them and delayed going to the clinic for weeks. The doctor said our son had an infection, but the drops didn’t work, and the white grew bigger. We went to the district hospital, and they sent us to the eye hospital that treats children for free. The doctor was kind when he told us about the cancer, but they only had surgery, not chemotherapy. By the time we got to the hospital that has chemotherapy and doctors who know retinoblastoma, we were more than a year from the first white seen by my wife. The cancer was through our son’s blood. He made a big fight in treatment, but we came to the hospital too late. I have great pain thinking how we talked about the white eye when we did not know it would kill our son.”

In most countries, parents are not systematically provided with information about important signs of eye problems to be alert to in their child. They have to rely on what they read or see in newspapers, television, and increasingly, on social media.

“It’s only in a photo, not in his eyes…it’s the camera.” [husband]

“…Yes it is! It could be a tumour… I read it on Facebook.” [wife]

Yet, parents of children diagnosed with retinoblastoma wonder why such important information is not provided.

“After our daughter was diagnosed with bilateral Rb at 18 months, we traced the white reflex back in photos to 11 months old. We had no idea about Rb or its symptoms before the diagnosis. This is such a simple sign for parents and photographers to look for, and easy to explain to people. … We would have remembered to look for this sign if we had been educated about it. Maybe our daughter would still have both eyes if she had been diagnosed when the white glow was first obvious in our family snaps.”

I cannot begin to imagine the pain and heartbreak a parent feels when faced with the realisation that the signs were there, but they just didn’t know the white glow or turned eye meant something. We talk a lot about the impact of delayed diagnosis on the child – whether their sight, eye or even their life might be saved. But what of the emotional impact delays have on their parents and family? Is it not enough that they experience the grief of their child’s diagnosis, gruelling treatment and side effects? What of the ‘what if’s…’ and ‘maybe if I had only…’ they carry too?

There has been no exploration of this impact in the medical literature, but as a clinician I am often asked “If we came sooner would the outcome have been different?” Sometimes it may not have made any difference at all, that is just how retinoblastoma is – an aggressive cancer. But the truthful answer is we don’t really know. We cannot focus on what we don’t know, but should rather focus our attentions on what we do…

Knowledge is Power…For Parents

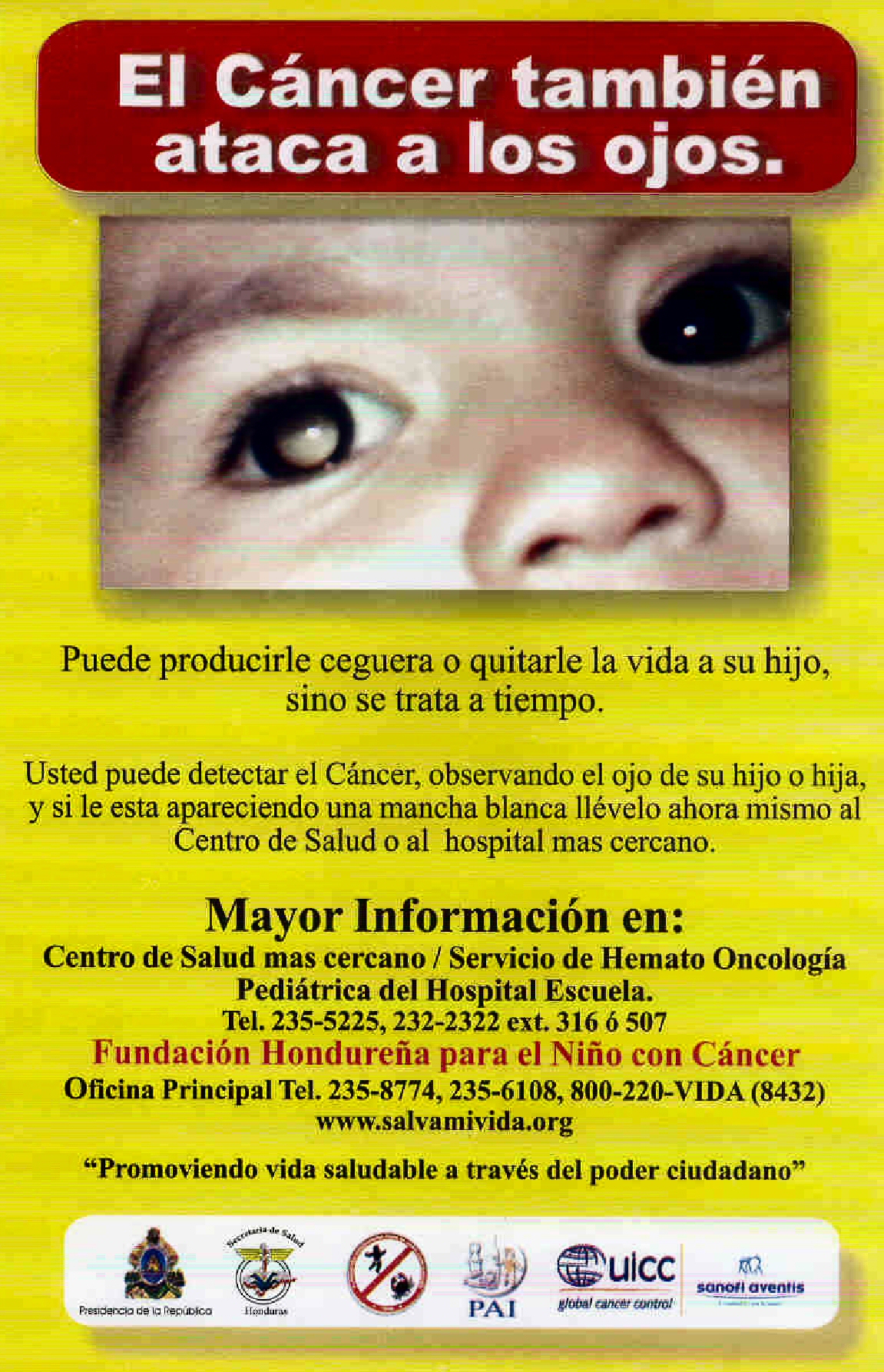

We do know that giving parents information works!! Published in 2007, a study by doctors and researchers in Honduras very clearly demonstrated that simply alerting parents to the sign of a white pupil can have a direct and measurable impact on a child’s survival from retinoblastoma. A simple poster including a photo of a child with a white pupil was displayed in community centres frequented by parents attending for their baby’s health checks and immunisations.

We do know that giving parents information works!! Published in 2007, a study by doctors and researchers in Honduras very clearly demonstrated that simply alerting parents to the sign of a white pupil can have a direct and measurable impact on a child’s survival from retinoblastoma. A simple poster including a photo of a child with a white pupil was displayed in community centres frequented by parents attending for their baby’s health checks and immunisations.

This was enough to forewarn parents of this sign and encourage them to seek advice from a health care worker if they were worried. Amazingly, coupled with re-educating healthcare providers, this approach resulted in a 3-fold increase in children surviving. This was simply because parents came when they noticed the white pupil rather than waiting until the disease had spread out of the eye.

This low-cost, simple and effective approach is what drives us to continue to promote the early signs of retinoblastoma – we know it works. But is it sustainable? Is there a more effective way to achieve the same goal? How can we be sure EVERY parent sees this information, is able to read or understand it, and importantly, know how to respond if concerned? Can they even access the treatment their child will need?

In some countries (Kenya, United Kingdom), we know that information about white pupils and turned eyes is being included in the infant health books so all parents are given the opportunity to be better informed. We don’t know yet whether these initiatives are having the impact we would like them to.

Knowledge is Power…For Researchers

The challenges we face as a community to raise awareness about the signs of retinoblastoma are numerous. A research project I conducted during my doctoral studies sought to understand the frequency of awareness programs conducted by health professionals or retinoblastoma-specific organisations around the world. I focused on the questions: 1) what did you do and how did you do it? Or 2) if you did nothing – why not?

After sending 146 emails to treatment centres registered on the One Retinoblastoma World map and retinoblastoma-specific charitable organisations, I received 30 responses from clinicians or organisations from both high-income (HIC) and low-middle income (LMIC) countries across six continents. Of these, 30% had NEVER conducted any specific awareness program in their country or city – and Australia was one of them.

The 70% who had done so relied heavily on philanthropy and charitable organisations to establish and continue their programs. It did not matter whether the organisation was in a HIC or LMIC – their challenges were the same. Money and human resources were the most common barrier to conducting awareness programs.

Giving parents important information such as this should not be dependent on charity. Is it not a right for every parent to be provided with information that enables them to look after their child’s life, health, and sight?

“Maybe They Think I’m Crazy?”

The white pupil and turned eye may not be present all the time, so it may be difficult to demonstrate it to friends and family for reassurance and advice. More critical still, it may not be evident when visiting the doctor. A parent may be too scared to say something to their doctor/health nurse, lest they be thought of as “a crazy, paranoid parent”, especially if other family members do not see the signs. These feelings of inadequacy and frustration can be difficult to negotiate or manage.

Moreover, seeing something and not being taken seriously, having one’s concerns dismissed, or worse, feeling judged as being paranoid or neurotic, can have a significant psychological impact on parents and caregivers.

“What is it with doctors who don’t listen to parents’ concerns? We saw the white eye glow so early, in photos and with our own eyes in dim light. We went to our family doctor repeatedly. We spoke to the pediatrician and to the breastfeeding nurse. None of them looked in her eyes and all of them said she was fine, even when I showed the doctor the photos. I want to scream now when I think about it, because I had already researched online, and I knew in my gut that she had Rb but they just told me I was a neurotic first-time mom. How can it be that parents know their kids have cancer when doctors are in denial about it and accuse the parent of being neurotic rather than doing their job properly? I know my experience is not uncommon.”

The feeling of being judged is not the only impact. Advocating for one’s child may not come so easily to some. Culturally or historically we are conditioned not to question a healthcare provider’s judgement; that we should simply trust their opinion rather than question their findings. This may be even more evident in LMIC or ethnic minorities in any country (HIC or LMIC) where specialist care may not be as readily available or accessible.

We don’t really know (yet) the challenges parents face in different countries when trying to obtain a diagnosis for their child. When we understand these barriers through further research, we will be better positioned to advocate for change.

Together with the Canadian Retinoblastoma Research Advisory Board, we are working on a research project to understand parents’ experiences relating to their child’s retinoblastoma diagnosis. We hope the study findings will help us decide what needs to change and where.

In the meantime, encouraging parents to show photos of their child, or a pamphlet or website about retinoblastoma, may empower them to speak confidently with their doctor. The visual tools can help them describe specifically what they have seen and why they are worried.

Letter F entry from the 2020 Alphabet of Hope: #FamilyInSight

Emotional Support… For Parents

Whether the time that passes from first seeing a white glow or turned eye is long or short, diagnosis will still come as a major shock to the parents, and then to their family. Feelings of disbelief, uncertainty for what their child’s future holds, and the decisions they are now faced with making are overwhelming. Providing parents with the space to process information and support them as they make treatment decisions can be equally challenging.

“I would like to ask you to please help newly diagnosed families connect faster with other parents and survivors. We didn’t meet any parents during our first visit because of the way everything happened at the hospital. It took me weeks to come out of my fog and search for “retinoblastoma” on Facebook. Then I found a crazy number of groups and pages and I went from having no connections to total overwhelm. It would have been so helpful if the doctor had given me a little card listing some resources. I would have loved to connect right away with at least one family who could encourage me and give me hope for my child by showing me they had come out the other side. I felt so desperately alone in the beginning.”

Parents receive volumes of information that we as clinicians expect they will understand, to guide them to make a decision about treatment that is right for their child and family. No matter how much experience I have in caring for families with retinoblastoma, my children do not have Rb and I cannot really know how it feels to make these decisions. So, at the time of diagnosis, I always offer parents the opportunity to talk with other parents who have walked in their shoes.

Not everyone takes up my offer of parent-to-parent support, and that is ok; each will draw on the resources provided to keep putting one foot in front of the other in those first stressful, rollercoaster days and weeks of diagnosis and treatment. Perhaps in the moment immediately following diagnosis, talking with other families sounds like a good idea, but in the quiet of their home and as the enormity of what lies ahead becomes more real, talking to others may just be too confronting.

I have seen first-hand though, the benefit that can be had from spending time with other parents on EUA day, whilst their children play together. The parent of the newly diagnosed child can see for themselves that a child with Rb still runs, jumps, laughs and plays despite having had an eye removed or poor vision. I like to think this is healing and helpful, dissipating their fears to a degree, and replacing them with feelings of hope that their child will be ok.

“I don’t like how some processes are structured so they are efficient for the doctors but cause me and my child unnecessary distress. For example, instead of making us wait for a long time in our private room, could we be in one place with other families? Our children could play together, and the time would go faster. … Our hospital visits are the only time we have to meet with other families who know what we are going through. Please don’t take that away from us by separating us into individual rooms.”

In my centre, we provide children the opportunity to play together whilst awaiting their procedure on EUA day, and their parents organically share support. Some great friendships have been forged over these 4-weekly visits, and I would like to think they each helped one another at a time when they needed it most.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, we were forced to separate our families into private rooms as they awaited their EUA – to keep them and us safe. Doing so reminded me how important those opportunities are; where parents brought together by a shared circumstance can talk with each other, compare stories, tips, and tricks, and most importantly not feel so alone.

We are now back to our “makeshift playroom” on EUA day; the parents and children, if but for a moment, forget why they are at the hospital, and can share their stories of treatment success or even failure, and hope.

Letter K entry from the 2019 Alphabet of Hope: #LifeBeyondRb

Knowledge is Power…For Survivor Care

Retinoblastoma is referred to, not affectionately I might add, as “the gift that just keeps giving”. Our knowledge and understanding of retinoblastoma genetics, treatment side-effects – both acute and long-term – and the risks for developing second cancers, has increased rapidly in the past 40 years, but there is still so much we don’t know. As with most things, the more we know, the more we realise we just don’t know enough.

“As a survivor of bilateral Rb, I am well aware of my second cancer risks. I have lost friends to other cancers, that I grew up with or met online. Every time I hear of someone who has another cancer, I think it could be me. I worry that me and my doctor will miss the warning signs and that it will be found late like so many Rb survivors I know. I would feel better if we could have regular scans or blood tests or something that would help us find the cancer early. Knowing my risk and not being able to do anything about it is heavy.”

The goal posts keep changing. As new treatments are developed, or the way old treatments are delivered, we need to start again to identify and monitor what the side-effects or long-term effects might be. It can take almost a lifetime to fully understand what impact the different treatment has had on a new generation of children.

Lifetime risks very, because not all children have the same treatment (including radiation or chemotherapy), or even the same type of disease (heritable versus non-heritable). Their needs for ongoing screening or surveillance will therefore also differ.

Understanding the individual’s lived experience of retinoblastoma and ongoing care will support the development of relevant and effective screening and broader survivorship programs. Particularly in terms of their fears about developing second cancers, and the challenges they face in seeking health advice and care.

Yes, retinoblastoma is rare; and yes, few healthcare providers will fully understand the ongoing healthcare needs and surveillance requirements for each individual. However, if we can provide survivors with the information they need to effectively advocate for themselves, and their primary physicians the resources they require to efficiently refer to relevant services, the survivor’s stress and experience of not being taken seriously may be lessened. Knowing that if they are worried, they can turn to an experienced medical professional who will help them navigate ‘the system’, should be a security available to all retinoblastoma survivors, wherever they live.

Again, research is critical to document the lived experiences of survivors navigating their health system, relating to second cancer surveillance. Only then can we show policy makers the gap that exists, and advocate to establish universal long-term follow-up programs.

Making Personal Choices Without Judgement

Over time, a child grows up to make their own choices. Dishearteningly, there are times when a healthcare provider may make a survivor feel “less than” human or impose their opinion on decisions that need to be made. Depending on whether the patient has heritable or non-heritable retinoblastoma, decisions they need to make about monitoring their health or family planning will differ. Each survivor should be encouraged and empowered to make decisions that are right for them. The clinician’s only role is to provide them with the information they require to make that decision.

“I had bilateral Rb. My ophthalmologist discouraged my partner and me from having kids due to the genetics and risk to our children. He thought we would be unable to cope as we both have poor sight. Educate about the genetics and the options available, but please never, ever express your opinion or push your prejudices on your patients. Having retinoblastoma and carrying the RB1 mutation is a deeply personal affair. The decision to create and raise a family is not yours to make or influence, or judge in any way.”

“I agree so much with the above comment [refers to the above parent/survivor quote]. In my mid-20s, I was hired at an adolescent home that required a physical as part of employment. The physical was done by the in-house pediatrician, who I had never seen before. When he asked about my eye and I told him, he said “you know you should never have children.” I was hurt and shocked, because I had never heard this. It was irresponsible of this doctor to make the statement, not knowing my history! As fate would have it, once I went through genetic testing, it was found I did not carry the gene [mutation]! What if I had listened to this doctor?! And – what led this doctor to believe life with Rb is all bad?! It isn’t, we’re survivors!”

Conversely, healthcare providers may expect the survivor to know more than them and feel ‘comfortable’ leaving them to navigate the health system for themselves. Many changes relating to treatment and outcomes occur from one generation to another; physicians should be encouraged to evaluate the evidence with survivors and guide them in their decision-making accordingly.

“I had Rb as a baby, and two of my children also did. I wish the doctors had given me more support when my children were going through treatment. I think the doctors thought that because I had Rb and am educated about it, I didn’t need more info or help. I was mostly left to figure things out alone. I am a survivor, but also a mom to kids with cancer. Despite my factual knowledge, I had no practical experience of the process and I was scared!”

It is critical that any person in a position of care or support remains alert to, and understanding of, the mental health impact on anyone with retinoblastoma – whether a child or an adult. For the child, the regular hospital visits and eye drops, or any intervention, can instil lifelong fears of procedures or separation. For the adult, risks for anxiety, depression and late diagnosis of second cancer are potentially high as they face a lifetime of navigating a system that does not understand, nor support their needs.

A Final Word

We are yet to fully understand the psychological impact on families and survivors resulting from lack of awareness among themselves and their health providers. Knowledge of not only the signs of retinoblastoma, but also the long-term effects of treatment and the life-time risks associated with this cancer syndrome.

Right now, though, we can continue raising awareness of retinoblastoma’s early signs for the broader community and healthcare providers and do all we can to provide survivors with the information and resources they require to proactively advocate for themselves for optimum health.

About the Author

Sandra Staffieri is the Retinoblastoma Care Co-ordinator at the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) Melbourne, Australia. Working at the RCH and in private clinics, she has over 35 years’ experience in children’s eye health and disease.

As a Research Fellow and Clinical Orthoptist at the Centre for Eye Research Australia, Sandra completed her PhD on delayed diagnosis of retinoblastoma. Her prime focus was to develop and evaluate an information pamphlet for new parents to raise awareness of the important signs of childhood eye disease – particularly strabismus and leukocoria – in the hope this could lead to earlier diagnosis.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!