10 Ways to Support Your Child Through EUA for Retinoblastoma

Monday March 4, 2019

Examinations Under Anaesthetic (EUA) are an essential part of retinoblastoma diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance follow up care. Combining content from our Child Life Resource, Morgan Livingstone CCLS CIMI MA reviews 10 ways parents can support children of all ages through the experience to benefit everyone’s wellbeing.

Examinations Under Anesthesia (EUA) is a routine procedure to examine a child’s eyes and monitor retinoblastoma while they are asleep. EUA is usually done in an operating room, but it is not itself an operation. Tests are done during the exam, and treatments may be done if the tests show they are needed.

EUA involves multiple experiences that can be potentially very stressful for a young child, including fasting, administration of eye drops, induction of anesthesia via a mask, and separation from a trusted parent. Fear, high stress and learned anticipation of distress can overwhelm a child’s natural ability to cope and co-operate. Medical trauma can delay healing and normal development, with lasting negative effects on their physical and mental health.

Yet simple child-friendly supports such as preparation medical play, distraction, and positions of comfort can make a significant difference to a child’s immediate and lifelong well-being. Whether you’re supporting a newborn infant, a toddler or older child, following the steps below will bring you and your child greater calm and confidence through every stage of the EUA process.

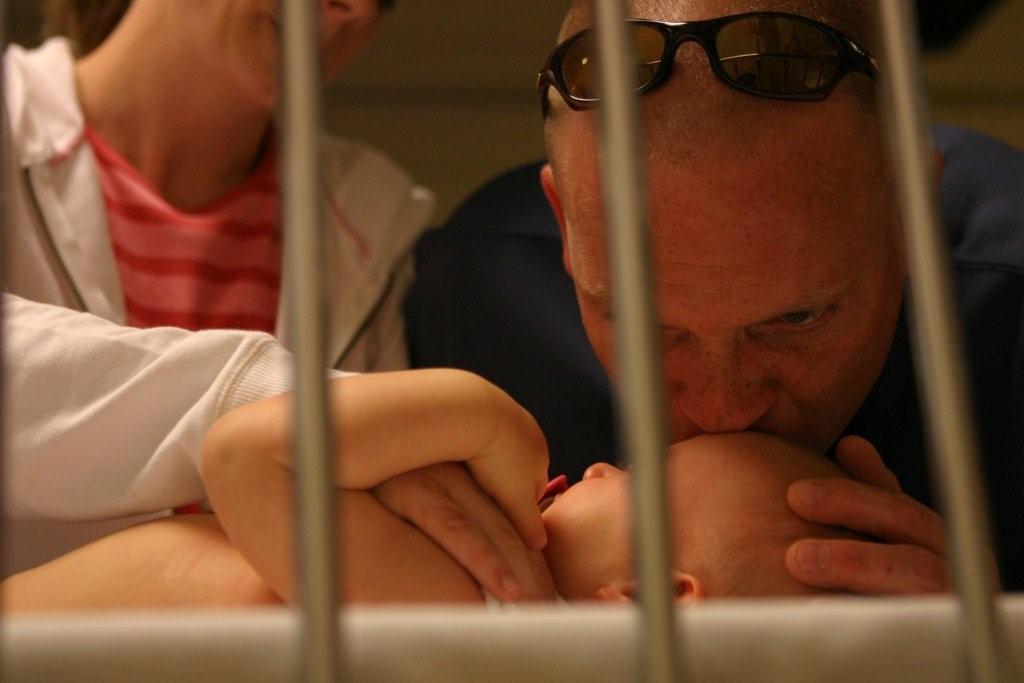

Playing with an anaesthetic mask, this child practices taking deep breaths in and out.

1. Manage Your Anxiety

Children learn from their parents’ behavior and tend to mirror their actions and emotions. Your child is constantly watching you, taking cues for how to respond to a situation, interaction or treatment procedure directly from your actions and responses. If you demonstrate anxiety and upset, your child will likely respond with anxiety and upset. If you stay calm, you will be more able to offer support, and your child will be more likely to stay calm too, and build confidence.

Be aware that your conversations with family, friends or medical professionals may be overheard and/or observed by your child. Bare this in mind when discussing your feelings about procedures with other people, whether by telephone or in person. Even if they can’t hear the full conversation, they may be able to pick up on your body language and tone of voice. Already stressed children can expertly fill gaps in their own minds where dark lines are drawn in this way.

Please ensure you seek out the support you need to assist you in reducing your own stress about the upcoming EUA. Take the necessary steps to ensure you remain calm during the period leading up to the procedure, so you can be present for your child.

Some helpful stress and anxiety reducing strategies are deep breathing, yoga, meditation, exercise, listening to uplifting music, participating in a favorite hobby or activity, connecting with parents who have already completed treatment and can help mentor you with positive support, talking to a counselor or therapist. In some cases, medication may be necessary to assist you with parental anxiety.

2. Embrace Medical Play

Medical play can greatly benefit all children with retinoblastoma. Through medically themed play with real or toy medical equipment, dolls and teddy bears, children safely learn to master medical procedures, process their own health care experience, and reduce their anxiety about the hospital environment.

All medical preparation play should be offered well before the scheduled EUA. Include it throughout the day during normal play opportunities. Try not to single out a specific “medical play time”, and give your child the opportunity to invite you into medical play when they want to explore it. Mix the mask, other medical toys and story books together with all the other toys, so they become a natural part of your child’s everyday play.

Hospital Visit Story Books

Read stories with your child about hospital experiences. They help acquaint children with people on the medical team, and the steps they may go through on EUA day. Mainstream book stores offer many children’s book about “Going to the Hospital”. You can also create your own step-by-step social story about your child’s visit to the clinic/hospital using photos of past visits. This example features my medical play puppet, Kamau.

Preparatory Coloring Books

Many hospitals have pre-surgical coloring books to help prepare children for what they will see and experience on EUA day. These books often discuss the sedation mask, operating room and recovery room. Ask a child life specialist or someone on your medical team if your hospital has such a preparation coloring book.

Pre-Surgery Hospital Tours

Some hospitals offer Pre-surgical tours. These can be a good way for a child to explore the events they will encounter on EUA day. The visit often includes a tour of the operating room and some facilitated medical play.

Share Your Praise

Let your child overhear you “bragging” about their success in mastering procedures for EUA. Tell the nurses and doctors about your child’s great skill of placing the mask on themselves and doing 10 deep breaths. Encourage your child to share with friends and family their amazing ability to have eye drops – so long as you feel comfortable sharing in it too. This will boost your child’s confidence and sense of mastery.

Two young children explore mask play with Morgan’s medical play puppet Kamau, during the child life program at the October 2017 One Rb World meeting in Washington D.C. Practicing the steps helps the children build confidence for their own procedure.

3. Prepare for the Sedation Mask

The main goals of preparatory mask play are to:

- familiarize your child with the sedation mask,

- show your child the mask will not hurt, and

- show the steps they will go through when being sedated.

Preparation varies for different age groups.

0-6 months

Sensitize your infant to the mask by gently placing it on their face, over their nose and mouth, while you relax together in a comfortable position. Sing a gentle song or count up to 10 or down from 10 to demonstrate the length of time the mask will be on your infant’s face before they are fully sedated.

7-18 months

Slightly older babies are naturally curious and want to explore everything around them. The sedation mask is something to touch, taste and manipulate with their hands.

Allow your baby to safely explore the mask through supervised play. Play will most likely include banging, throwing, biting, chewing and squeezing the mask with their hands.

Babies like to mimic their parents’ actions (remember how much fun peek-a-boo is). So when your child is familiar with how the mask feels, demonstrate its correct use by putting it on your face. Say aloud “Mask on Daddy’s face”, “Put on”, “Over Mommy’s nose and mouth” to explain your actions. Repeat this several times to ensure your baby understands the action.

Then place the mask on your baby’s face. Pass the mask to your baby and encourage them to copy your actions. Say aloud “Your turn, put on”, “Nose and mouth”, “Mask on (Baby’s Name)”.

As your baby masters this action, you can add another step to your play – taking a deep breath and blowing out. Older babies should be able to mimic this action, while younger babies may take some time to coordinate the breathing/blowing action.

As a final step in your mask play, count to 10 while the mask is over your baby’s face. Alternatively, sing a short song of similar length to help your child prepare for the length of time the mask is in place during anesthesia induction.

18 months to 2.5 years

Toddlers typically want to do things “their way” or not at all. Many like to show people around them how they have mastered a specific skill, and look forward to receiving praise for successfully demonstrating this.

Set your toddler up for success by incorporating mask play into regular playtime. Practice placing the mask on Mommy or Daddy’s face, and then placing the mask on your toddler’s face. Taking turns is fun for a toddler, so be prepared to practice this many times.

Use simple language to label and explain each step (as described in the 7-18 month section). Include holding over the nose and mouth, breathing in and out, and counting to 10. When your toddler completes all the steps, offer lots of praise, hugs and positive attention.

2.5 years+

All children will benefit from medical play using the approaches described above. Slightly older children will enjoy longer sessions with more back and forth mask play. They may also incorporate touching their eyes, associating the anesthesia with examination of their eyes while asleep. Repetition through play allows the child to understand and master the steps in the sedation procedure, and gain greater familiarity and confidence with the mask and entire EUA process.

4. Follow Food / Fluid Restriction Instructions

The hospital will give you strict instructions to follow in the hours immediately before the EUA. This will include that your child should eat no solid food for 6-8 hours before anesthesia.

Typically, children will be allowed clear liquids up to two hours before surgery. Clear liquids may include apple juice, grape juice, cranberry/raspberry juice, or water, but no opaque drinks such as orange juice, milk or yogurt drinks.

Breastfeeding is usually allowed up-to four hours before anesthesia, with clear fluids allowed as above to two hours prior. Some hospitals allow breastfeeding up-to two hours prior for very young babies and specific medical situations. If you are breastfeeding, ask your baby’s care team specifically how late before anesthesia you can give breast milk.

Since many children are booked for an early morning EUA, you will typically be instructed to not allow any food or drink to be taken by mouth after midnight. Please listen closely to the medical staff as they explain these restrictions, and ensure you follow them completely. If you allow your child to eat within 6 hours of the EUA, it may be delayed or even postponed to another day, at significant cost and distress.

5. Be Practical on EUA Day

On arrival at the hospital, you will register and most likely need to change your child into a hospital gown or pajamas. To avoid this step of changing clothes, some parents find it helpful to bring their child to the hospital already dressed in pajamas.

All hospitals require some waiting. Ensure you pack appropriate toys and personal items to support your child and yourself through what can be long hours of waiting. Avoid toys, games and books featuring or associated with food as these are challenging for children who are not allowed to eat before anesthesia.

For the same reason, please do not eat around your child and other children. If you must eat for medical reasons, arrange in advance with your partner or other person accompanying you to watch your child for a few minutes while you go elsewhere. If you are attending the EUA alone, ask another parent for assistance. Be sensitive to children’s restrictions as you explain your reasons, and offer to return the favor. Be aware that your child may be more anxious about your absence today. Prepare them appropriately with compassion and patience, and return quickly.

Some hospitals allow children to bring their special toy, stuffed animal or blanket into the Operating Room. The staff will often place a hospital bracelet on that personal item when the child receives their bracelet. This supports the child, denotes that the item has been approved, and ensures it can be identified if it is later misplaced.

6. Practice Giving Eye Drops

Before the EUA, eye drops will be administered to dilate your child’s pupils. If your child has a successful preferred method for delivery of eye drops, you should advocate for this early on. Some nurses will allow you to administer the drops yourself, if you and your child are comfortable with this.

Practice

If you and your child struggle with eye drops, practice repeatedly before the EUA to find what works best for both of you. Take turns giving pretend eye drops to one another. Allow your child to practice putting plain water drops or artificial tears into your eyes or into a doll or stuffed animal’s eyes. This promotes a positive experience and helps them gain familiarity and mastery, confidence and a sense of control over their fear. Older children can begin practice with water drops or artificial tears, and work their way up to administering eye drops on themselves whenever possible.

Comfort Positions

Many children do not feel comfortable lying on their back during medical procedures. This can cause them to feel exposed, vulnerable and upset. Explore different comfort positions. Allow your child to practice giving drops into a doll’s eyes in the different positions you practice. This will add to the sense of mastery and control over their experience.

Positive Language

Practice a calm voice and supportive language. Encourage your child during delivery of the drops. Tell him how well he is doing. If the drops sting, remind him they hurt only for a few moments. Help your child focus on looking up while lightly blinking their eyes to help the drops absorb. If the drops don’t sting, tell him they will only feel cool and wet – like the practice drops.

Distraction

Encourage your child to choose a special song to sing when the eye drops are given, or a nursery rhyme to say. Some drops can sting for up-to a minute, so try to pick a distraction that will occupy your child for at least two minutes. Reading a book to your child can be a great distraction, but remember your child will not be able to see pictures or read the text during delivery of the drops or for a little while afterwards. So don’t base distraction on visual stimuli.

A young boy practices giving eye drops to Morgan’s medical play puppet Sunny, and to Elli the elephant during the child life program at the Canadian Rb Research Advisory Board meeting in January 2019. This promotes a sense of mastery and familiarity, so he can be and feel successful during his own drops.

7. Prepare for Pre-Anesthesia

Some hospitals give pre-anesthesia medication, either routinely or when a child appears anxious or upset about the approaching sedation and procedure. Sometimes called a “pre-med”, this medicine is intended to relax a child and can be given as an oral liquid or an injection. Not all children need a “pre-med”.

If you feel your child may be anxious or upset on EUA day, check with your hospital about what medicines they can give to your child before the procedure. Ask how this medicine is administered, and then practice this method with your child through play in the weeks leading up to the EUA.

If the medicine will be given orally (usually with a syringe), practice giving your child juice with a medication syringe. If via injection, practice Positions for Comfort to find the one you and your child feel most comfortable with for receiving an injection.

8. Encourage Your Child Going Into the Operating Room

Many hospitals allow a parent to be present during anesthesia induction. The parent is typically given a large sterile suit to wear over their clothes, before they walk alongside or carry their child into the OR. They can hug and hold their child, and give words of encouragement, while the anesthesiologist places the mask on the child and administers the sedation. Once the child is sedated, the parent leaves the OR.

In hospitals that don’t allow parental presence anesthesia induction, a member of the medical team will collect the child from the waiting room or ward. Many hospitals allow a child to select their mode of transport into the OR – walking, being carried, or riding in a wheelchair. Sometimes children can ride a large plastic car or wagon.

In either scenario, parents need to stay positive for the child’s wellbeing. If your hospital offers a Hug and Hold program but you feel you will not be a good support for your child during the induction of anesthesia, it is important to say so, and consider following the steps below instead.

If you cannot accompany your child into the OR, greet the medical team member warmly when they come for your child. Show your child that you trust this person and you’re happy for them to go together without you. Remind your child to look for the mask in the OR and show the nurse/doctor they know how to use it.

Many children who have confidence in the mask through preparatory play are very excited to show off their skills. The fear of separation is avoided completely as they strain to get into the OR and find the mask.

9. Support Your Recovering Child

After the EUA, your child will be taken into the recovery room. Some hospitals allow parents to be present while their child wakes up from sedation. Other hospitals require parents to wait until their child is fully awake before they are allowed to enter the recovery area. Yet other hospitals only reunite children with parents on the ward.

Ask your medical team before the EUA what the recovery plan and timeline will be, so you are well prepared. Ask who your contact person will be if you have any questions or need an update during the EUA and recovery. Wherever possible, advocate to be present when your child wakes up, if this is important to them.

Some children sleep for up-to an hour after anesthesia. This is normal and your child will be closely monitored by skilled nurses at all times.

Some children are confused, upset or restless on waking. This is a normal effect of the medicine as it wears off. Crying and deep breathing actually helps the child’s body remove the medicine. Comfort your child with gentle words and positive touch as you wait for them to become more alert.

Children are often hungry and thirsty after the EUA. The nurses will offer clear fluids – juice and sometimes popsicles. Babies can be given breast milk at this time. Not all hospitals offer a variety of juices. If your child has a favourite clear drink, consider bringing it as a special treat to look forward to. Do not label it in advance as a reward for good behaviour – this places a significantly different meaning on the drink, which is needed in this situation to aid your child’s physical recovery.

10. Ask Questions Before You Leave

Before you leave the hospital, or move to a different department for further treatment, ask all the questions you need to. Here is a checklist of questions to ask:

- What tests were done during the EUA and what did they show?

- Can I see / have copies of the Retcam images / ultrasounds / fundus drawings?

- Is the optic nerve visible (in each eye with Rb)?

- What treatments were done, if any, and why? Or why not?

- When will the next EUA be? Why?

- What is the EUA scheduling process, and what’s the process if I feel the EUA should be brought forward?

If you feel you and your child would benefit from more preparation play to improve coping during future EUAs, ask if you can be referred to a child life / play specialist for some 1:1 sessions. Professionally supported medical play, and individualized guidance for play sessions at home, can be hugely valuable for both parent and child in preparing for and mastering routine medical procedures.

Reducing Trauma, Building Confidence

EUA day, and the anticipation of it, can be incredibly stressful for both parents and children, but with self-care and preparation, you and your child can have greater confidence, calm and success through every step of the process.

Recognizing and honoring your own needs is vital for your physical and mental health and will enable you to be more present and supportive for your child. Embracing medical play provides endless opportunities for you and your child to learn about and develop confidence with the procedures involved in EUA, including eye drops and the sedation mask. Planning in advance for the practicalities of the day enables you to be a more prepared, relaxed and focused advocate.

By following these ten steps, you and your child can dramatically improve how you each experience EUAs for retinoblastoma, how your child understands the medical procedures involved, how they engage with their care, and how they continue to grow physically and emotionally through their cancer journey. You can actively reduce their exposure to stress, tension and trauma, and nurture their positive wellbeing throughout treatment and follow-up care. Each EUA will also become a building block, helping to construct positive associations with medical care – vital for your child who needs long-term follow-up care.

About the Author

Morgan Livingstone is a Certified Child Life Specialist and Certified Infant Massage Instructor/Trainer. She is passionate about improved child life and psychosocial supports for children and families affected by retinoblastoma.

Morgan Livingstone is a Certified Child Life Specialist and Certified Infant Massage Instructor/Trainer. She is passionate about improved child life and psychosocial supports for children and families affected by retinoblastoma.

As the Child Life Officer of World Eye Cancer Hope, Morgan contributes to the website’s Child Life sections, and speaks globally about child life supports for children with retinoblastoma. Morgan provided enriched multi-day child life programming for children of all ages at both One Rb World in Washington, D.C. in October 2017 and the Canadian Retinoblastoma Research Advisory Board meeting in December 2017.

Morgan also writes and creates resources for children and adults, and participates in child life research studies. She won the inaugural Innovation Grant at Operation Smile for developing an APP that uses Virtual Reality to prepare children receiving cleft lip and palate surgery for their operation.

Download Morgan’s helpful parent manual for supporting children’s worries using Worry Eaters.

Share this entry