Social Media Support: 10 Reasons Why Exchanging Medical Advice can be Unhelpful, and What to do Instead

Monday February 15, 2021

When someone asks for support on social media, instinct drives us to offer hopeful solutions. But without full knowledge and understanding, we may cause more harm than help. Reviewing real interactions and their outcomes, WE C Hope CEO, Abby White, shares key points to consider when discussing retinoblastoma, and how to respond well.

Human nature compels us to help one another, especially when a child is involved, or we see others hurting as we have. No one wants to think about children with eye cancer and their families suffering, and when families seek our support on social media, instincts drive us to rush in with hopeful solutions to ease the pain.

We want to help, but without understanding and full knowledge of the individual’s medical circumstances, we may send out unhelpful, or potentially very harmful responses. We risk causing more suffering to both the child or survivor and their entire family.

So what can we do to ensure our responses are encouraging and helpful?

Below, we share 10 points to consider when communicating in the retinoblastoma community. We describe interactions that occurred on social media, and key issues arising from them. Identities have been changed to protect the individuals’ privacy. We conclude this two-part article with 7 ways you can respond positively to any request for help, to improve communication and support.

Go to Part 2: Social Media Support: 7 Ways to Respond Effectively

1. Do You Have Relevant Knowledge and Experience?

Stacey posted photos of her daughter with bright leukocoria in one eye. She explained that Emma had already been examined by an ophthalmologist who saw no major issues and planned follow up with an eye exam under anaesthesia (EUA) for 4 weeks later. She asked parents their experiences of retinoblastoma diagnosis, and if she should be concerned.

In subsequent discussion, Stacey clarified that two-year-old Emma was seen by an ocular oncologist at a leading eye centre. Several parents confirmed the doctor’s expertise in diagnosing and treating their children.

However, most replies suggested or declared that Emma had retinoblastoma, and a second opinion was urgently needed. The skills and integrity of the ocular oncologist were questioned, and members suggested consulting with retinoblastoma specialist centres in different states, and even across international borders.

Some respondents pointed out that other eye conditions can cause leukocoria, and that retinoblastoma would be large to cause consistent white reflex in photos. Such a large tumour would be visible on clinical exam by an ocular oncologist, who would not ignore risk to the child. However, the strength of the majority response drowned out these wise words.

These responses were surely driven by personal experience and awareness of delayed diagnosis, understanding the impact of untreated retinoblastoma, and wishing the best for Emma and her family. But personal experience alone does not qualify us as experts in all aspects of retinoblastoma and eye or cancer care. Lack of broad knowledge, and inability to consider other possibilities, led to much incorrect information, poor advice, and unjust criticism of an experienced medical professional who had provided appropriate care.

Only one of these siz children has retinoblastoma, and only one has 2 healthy eyes. Can you identify them? Clockwise from top left: 1) Coats Disease, 2) normal optic nerve reflex, 3) cataract, 4) ocular albinism, 5) retinoblastoma, 6) anisometropia (severe refractive error).

2. Do You Know the Person’s Relevant Medical History?

Jonathan, a unilateral retinoblastoma survivor in his early 20s, requested advice about appropriate follow up care. Respondents shared information about high second cancer risk and advised 6-12 monthly whole body MRIs.

Moderators asked what treatment Jonathan had received and whether genetic testing had been done. He clarified that he had been treated with enucleation only at 19 months old, and genetic testing results showed less than 1% risk for heritable retinoblastoma. This means his second cancer risk is close to the normal population risk, and he therefore does not need ongoing oncology follow-up.

Jonathan was already confused and scared about second cancers when he posted his question. Lacking understanding about his treatment and genetic status, he did not include all the relevant information in his initial question. His parents received genetic counselling when his results were first returned, but he had not been informed as he grew up. In the rush to give information and support, group members failed to ask simple clarifying questions, or themselves lacked understanding of lifetime second cancer risk, unintentionally causing him more needless alarm.

3. Do You Know Where the Family Live?

Amal was diagnosed with bilateral retinoblastoma in India. Though his mother, Bela, did not include her country of residence in her first post, a quick glance at the “About” section of her Facebook profile gave me this information. Group members failed to note this fact and recommended urgent travel to various US treatment centres. Even after I signposted the family to expert centres in India, several members advised treatment in the US as offering the best chance to save one or both eyes.

India has a comprehensive national network of well resourced, highly skilled and experienced retinoblastoma specialist teams. Implying that Amal would have a better outcome in another country is insulting to those dedicated medical professionals, and severely undermines parent trust in locally available care. The family did ultimately receive care in India, with support of several local childhood cancer charities, but the responses they received on social media caused them to question their decisions and delay vital care.

4. Do You Know the Family’s Socioeconomic Circumstances?

Leah was diagnosed with retinoblastoma that had already spread to the brain. Without establishing any other circumstances, many parents advised that her family travel urgently to specific hospitals in the US, Canada, the UK, or Australia.

With a few simple questions, group moderators discerned Leah’s family live in the Philippines, where they struggled even to fund local bus fares. International travel was unrealistic and inappropriate for stage 4 retinoblastoma, giving false hope rather than compassionate support.

In both the above examples, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis was recommended as a solution if the family could not afford expensive care abroad, due to the hospital’s reputation for funding all aspects of patient care. But this impression of the hospital is often misrepresented.

To be accepted at St. Jude, children must be eligible for one of the hospital’s open clinical trials. Requirements for acceptance include age range; type and state of disease; and other medical criteria including organ function, blood values, and performance scores (a measure of how well the patient can continue daily activities, and estimate of the treatments they may tolerate). Some St. Jude trials accept children only if they have not yet begun treatment. Patients must also be referred by a physician or qualified medical professional. Families should keep all these points in mind if considering seeking a physician referral to St. Jude.

While St Jude families never receive a bill for treatment, travel, housing or food, the hospital is not a magic solution for every suffering child. However, St Jude Global, World Child Cancer, the International Society of Paediatric Oncology, and One Rb World are expanding hope to thousands of families through twinning partnerships and knowledge sharing that build in-country expertise, resources, and family support.

The twinning program in Davao, Philippines ultimately cared for Leah until she died, thanks to one dedicated American Rb Mom. Though she knew she’d likely never meet the family, and treatment was almost certainly palliative, she was compelled to sponsor and fundraise the costs of travel and care not covered locally, as she would wish someone to do for her own child.

Attendees work together during a breakout session at One Rb World 2014 in Toronto, Canada.

5. Do You Know What Obstacles May Limit Access to Care?

Michael was in the process of being accepted for treatment at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, located in a neighbouring state, when his mum, Helen, posted for the first time on a social media support group. A discussion arose about which treatments are offered at St Jude and other hospitals, and recommendations from other parents led to a second opinion.

Michael subsequently began treatment at another well-known retinoblastoma centre, despite the family’s lack of comprehensive medical insurance and inability to fund care, and significantly greater distance from home. His family did not qualify for many travel and other assistance programs, having income just above the threshold, but not sufficient to cover their increased costs.

When the financial burden of travel and treatment costs began to spiral, the family sought to transfer care closer to home. Only then did they discover that they had forfeited the chance of care at St Jude when treatment began elsewhere (refer to point #4, above).

6. Will You Undermine Trust in Local Expert Physicians?

Julia was diagnosed with unilateral Group E retinoblastoma. Enucleation was advised at a US regional comprehensive childhood cancer centre with retinoblastoma experience, though not a specialist Rb program. Numerous recommendations pointed her mother to a major specialist centre that was out-of-network for insurance coverage. After a two-week delay investigating various workarounds, her family paid out-of-pocket for consultation at the recommended hospital. Eye-salvage therapy began at the same hospital. One year later, Julia’s eye was removed due to progression of the cancer. Her family later lost their home, which had been re-mortgaged to cover the cost of uninsured treatment.

One-year old Karina was diagnosed with unilateral Group D retinoblastoma in India, and immediate enucleation was advised. Many encouraging stories of recovery and successful life after enucleation were shared in response in response to her father’s post, but stories of eye salvage were more abundant and passionate. Jamil and his family began to question locally recommended treatment. They followed advice to seek a second opinion, but lack of financial resources slowed this process, delaying removal of Karina’s eye by two months.

Positive pathology led to expensive chemotherapy her family struggled to pay for and comply with – they missed several treatments due to lack of funds. Karina’s cancer returned in her brain one year later, and she died just after her third birthday.

Many factors are taken into consideration when doctors recommend treatment for retinoblastoma. Social media posts by their nature are short, and most often do not include all the information needed to support an informed treatment decision.

7. Do You Understand the Potential Risks?

Hannah wrote that doctors advised enucleation for her two year old daughter, Grace, newly diagnosed with unilateral Group E retinoblastoma. She asked what experience others had of enucleation, or eye salvage treatment.

Many parents and survivors shared encouraging experience of enucleation. The majority response focused on eye salvage, including parents whose children had less advanced cancer at diagnosis. Several parents described how their children, diagnosed with Group E unilateral retinoblastoma, were successfully treated with a combination of therapies.

Grace’s family opted for eye salvage therapy, but it sadly failed to prevent enucleation of her eye one year later. She required chemotherapy even after her eye was removed as pathology showed a high risk that the cancer had already spread.

One child’s good outcome does not mean another child will have the same outcome with the same treatment, even if they appear to have the same diagnosis. Though the children were all staged with Group E retinoblastoma, they may have been staged differently using the new TNMH system. The eyes of the children for whom eye salvage was successful may have been staged TNMH t2b, while Grace may have been staged TNMH t3 – indicating a significant risk of cancer spreading beyond her eye at diagnosis.

Extract of a summary comparison chart showing TNM staging and other retinoblastoma staging systems used today. View the full PDF Summary document.

8. Does Your Response Add Clarity?

Liyana was diagnosed in Pakistan, with orbital and significant optic nerve invasion of retinoblastoma visible on MRI. Her father, Rayan, asked if it was possible to cure. Concerned respondents suggested treatment centres in other countries, discussed enucleation and eye salvage treatments, specific chemotherapy drugs and treatments being more or less viable based on Liyana’s age of 5 years.

This chain of discussion included multiple unqualified opinions based on personal experience, rather than evidence specific to Liyana’s diagnosis. For example, eye-salvage is not possible as part of life-saving care when retinoblastoma has already spread beyond the eye, and suggesting such an option is highly problematic for effective care.

Discussion by members and moderators arose around what was and was not helpful to share. Comments were at times heated and disrespectful. This would have been a very overwhelming and confusing jumble of responses for Rayan, who was, at heart, looking for comfort, encouragement and connection with other parents.

9. Are You Answering the Question?

Three month old Eli was diagnosed with a unilateral Group D tumour, having no family history of retinoblastoma. Specialists proposed enucleation or systemic chemotherapy, and Eli’s mother asked parents for their experiences with either option.

Responses included strong recommendations for treatment not proposed by the diagnosing medical team. Discussion about the appropriateness of these responses became heated, and the quiet voices of those who answered the original question were lost.

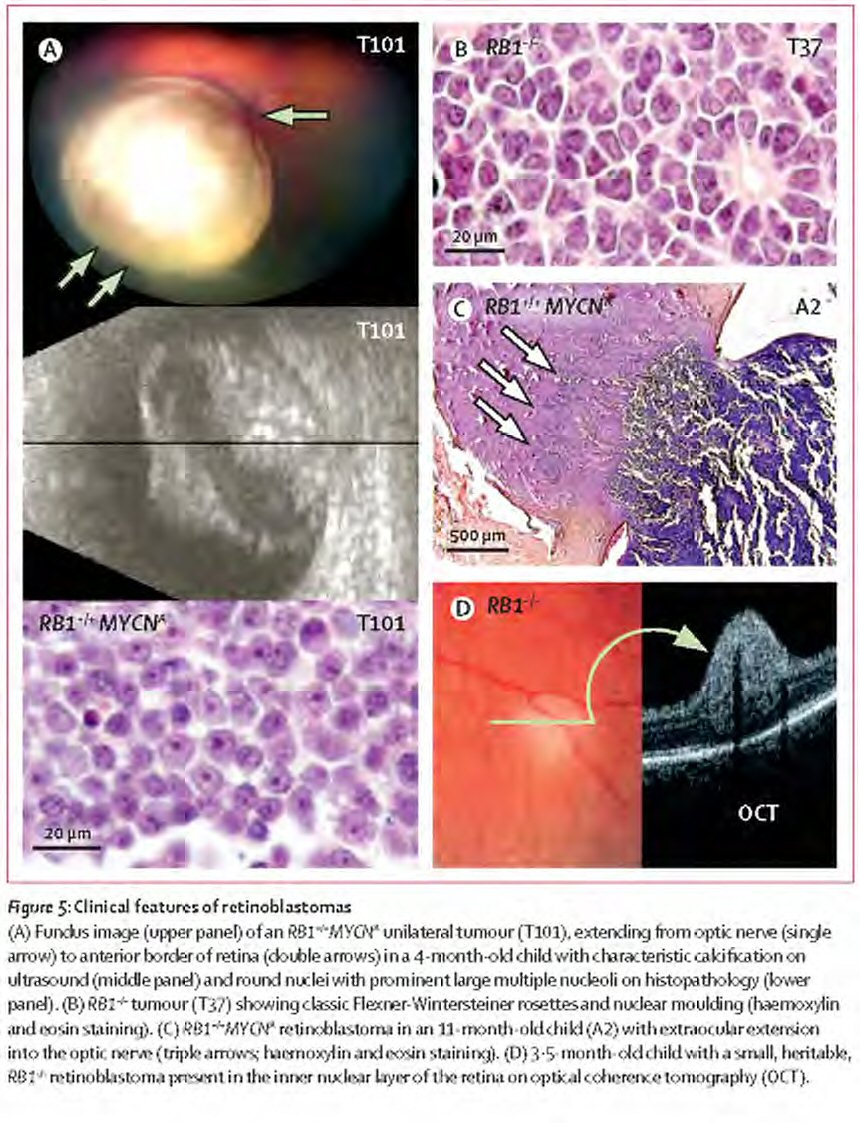

In this situation, enucleation and systemic chemotherapy specifically were proposed due to the advanced nature of Eli’s cancer and his young age. With only one tumour in one eye and no family history, the possibility of aggressive MYCN initiated retinoblastoma was high, but this could only be confirmed with enucleation and genetic testing of the tumour.

MYCN retinoblastoma poses no risk to the other eye, but its aggressive nature poses high risk for rapid spread beyond the eye. Therefore, eye-salvage treatment should take account of the risk for MYCN retinoblastoma, and include systemic chemotherapy to protect the child’s life.

Opinions are best kept in conversation about specific medical topics where valuable discussion with multiple viewpoints can help advance care. They may be confrontational, inflammatory, and very harmful in discussions about individual patient care, especially when key points about care are poorly understood.

Figure reprinted from The Lancet Oncology, Vol. 14. Rushlow, D, et al. Characterisation of retinoblastomas without RB1 mutations: genomic, gene expression, and clinical studies. Epub ahead of print. © (2013), with permission from Elsevier.

10. What Do You Need?

Reading diagnosis and treatment related posts from others can be highly emotive. They may trigger a resurgence of strong emotions felt and questions asked during your child’s diagnosis or treatment, or related to your own care and survivorship.

Are you writing your response primarily for the parent/survivor, or to help you process your own retinoblastoma experience, the grief, fears, and frustrations that arise from it, and the complex facts of care? Processing is very natural and healthy, and it’s ongoing. But it’s important to stop and ask yourself if this conversation with the parent or survivor is the best forum for your response. Can you add to or begin another conversation to share your thoughts more appropriately?

What can you do to reduce your stress when communications in the retinoblastoma social media community grow intense? Create a self-care action plan to help you decompress quickly. Try some of these 45 practical approaches to help calm body and mind. Practice them when you feel calm, so they become familiar. You’re more likely to use them when you most need them if you’ve already practiced, prepared, and have supplies to hand.

Consider sharing your story with WE C Hope – writing can be very therapeutic, and telling your story in detail is hugely valuable for other families. You can then also link to your story for other parents to read.

Read Part II of this article to discover 7 simple ways you can make any interaction with a parent or survivor in the retinoblastoma community more supportive and encouraging.

About the Author

Abby’s father was diagnosed with bilateral retinoblastoma in Kenya in 1946. Abby was also born with cancer in both eyes. She has an artificial eye and limited vision in her left eye that is now failing due to late effects of radiotherapy in infancy.

Abby studied geography at university, with emphasis on development in sub-Saharan Africa. She co-founded WE C Hope with Brenda Gallie, responding to the needs of one child and the desire to help many in developing countries. After receiving many requests for help from American families and adult survivors, she co-founded the US chapter to bring hope and encourage action across the country.

Abby enjoys listening to audio books, creative writing, open water swimming and long country walks.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!