New Form of Non-Heritable Retinoblastoma Discovered With NO RB1 Mutation

Wednesday March 13, 2013 | Abby White, WE C Hope CEO

Lucy was diagnosed at age 5 months with cancer filling her left eye. As she was so young, her doctors feared she would develop cancer in her right eye also. She began chemotherapy in attempts to shrink the cancer and save her eye. Sadly this did not work and at ten months old she received five weeks of radiotherapy. This too failed to stop her cancer growing, and her eye was eventually removed the day before her first birthday.

Two weeks later, Lucy’s family were devastated to learn she needed more chemotherapy and radiotherapy as cancer cells had been found outside her eye.

Three years later, Lucy is a healthy pre-schooler. She did not develop retinoblastoma in her other eye, and genetic testing could find no RB1 mutation in her tumour or blood. Samples of her bone marrow and spinal fluid are examined every 4 months to check that her cancer has not returned. She is working with therapists to help her through developmental delays and emotional challenges that may be a result of sustained invasive treatment at an early age.

Why did Lucy have such advanced retinoblastoma at diagnosis, when she apparently does not have a heritable RB1 mutation?

The desire to answer a parent’s question “why?” has laid a pathway to understanding of how more common cancers form. Today, discovery of a new rare subtype enables us to tell even more families what caused their child’s eye cancer, but also challenges the widely accepted view that all retinoblastoma is caused by mutation of the RB1 gene.

RB1 was the first tumour suppressor gene ever identified. Following its discovery in Boston in the early 80s, research has documented progression of retinoblastoma from benign tumour to malignant cancer. Loss of both RB1 genes in a single cell prompts benign retinoma. Successive mutations on other genes determine the strength of malignancy.

50% of children with retinoblastoma carry a constitutional RB1 mutation that predisposes them to retinoblastoma. This is either inherited from a parent or occurs early in foetal development.

The other 50% of children with retinoblastoma have unilateral retinoblastoma that occurs due to genetic changes in only one retinal cell. Mutation of both RB1 genes (RB1–/–) is accepted as the cause of all retinoblastoma, both heritable and non-heritable.

In the course of recent RB1 research, several labs worldwide found a small but consistent number of very young children with advanced unilateral retinoblastoma appeared to have two fully intact RB1 genes within their tumour. The researchers began to hypothesize that a genetic process other than RB1 was causing the cancer, and formed an international group to investigate their shared theory. Their findings are published today in the Lancet Oncology journal.

Led by Prof. Brenda Gallie and Impact Genetics (formerly Retinoblastoma Solutions) in Toronto (Canada), the team included researchers from Paris (France), Essen (Germany), Amsterdam (Netherlands) and Christchurch (New Zealand). They studied tumours from 1068 children with unilateral non-familial Rb, comparing those with no evidence of RB1 mutations (RB1+/+) with tumours carrying a mutation in both RB1 genes (RB1–/–).

No RB1 mutations (RB1+/+) were found in 29 (2·7%) tumours. They looked closely at genes that become mutated once RB1 is damaged in classic RB1-/- retinoblastoma. 15 of the 29 RB1+/+ tumours had amplification (more copies than normal) of MYCN (pronounced “Mick-En”). None of RB1–/– tumours showed MYCN amplification. Subsequent extensive studies confirmed the discovery, and determined this form of the disease accounts for about 1.4% of unilateral non-familial retinoblastoma.

This newly identified retinoblastoma subtype is called “RB1+/+MYCNA”. The +/+ indicates both copies of the RB1 gene are normal. The “A” stands for Amplification (too many copies) of MYCN).

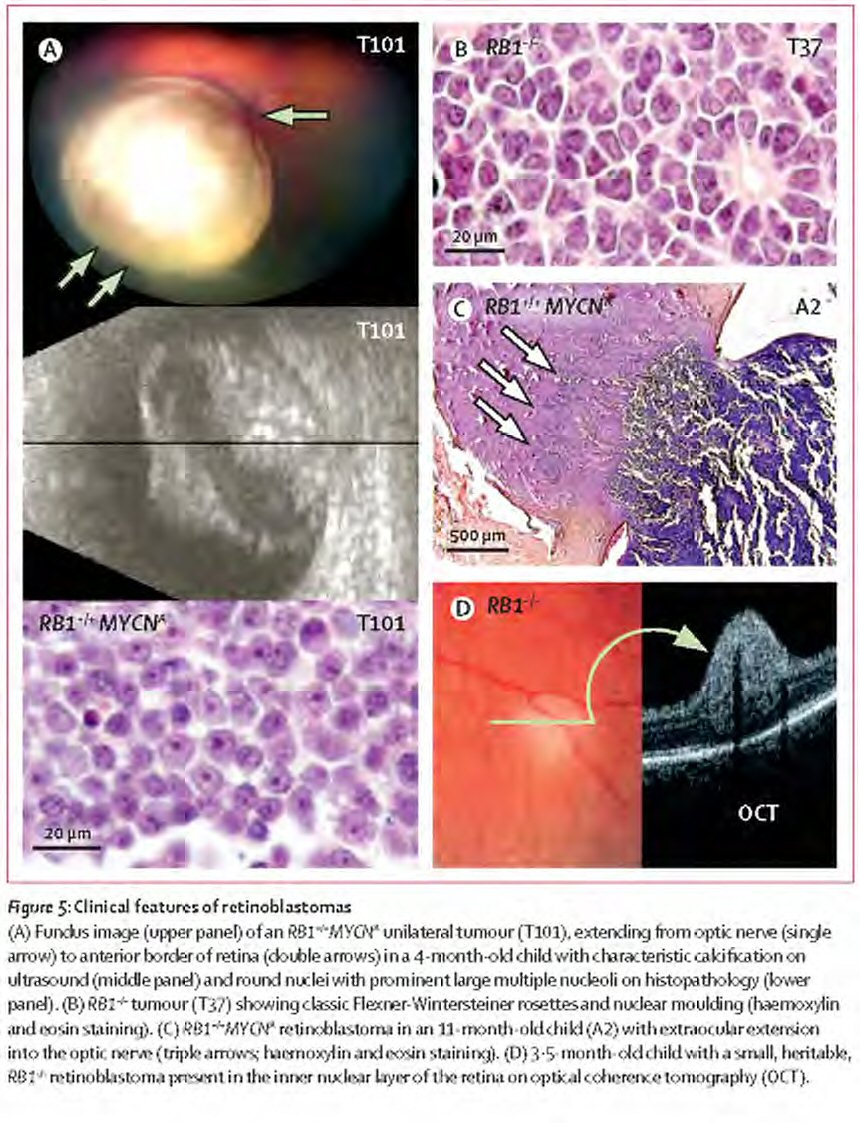

Amplification of the MYCN gene is most commonly associated with high risk, poor outcome neuroblastoma. Study of the RB1+/+MYCNA tumours under microscope revealed features of high risk neuroblastoma, though they were all technically retinoblastoma, arising from immature retinal cells.

All children with MYCNA retinoblastoma have one tumour in one eye that is highly aggressive and becomes very dangerous at an early age. Children of equivalent age with RB1 mutation usually have much smaller tumours at diagnosis.

Differences between MYCNA and RB1 Retinoblastoma. Figure reprinted from The Lancet Oncology, Vol. 14. Rushlow, D, et al. Characterisation of retinoblastomas without RB1 mutations: genomic, gene expression, and clinical studies. Epub ahead of print. Copyright (2013), with permission from Elsevier (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/14702045).

Average age at diagnosis of MYCNA retinoblastoma is 4.5 months, compared to 24 months for RB1-/- unilateral retinoblastoma with no family history, and 12 months for bilateral or unilateral cancer in children with the heritable form. Risk for a baby diagnosed unilateral at 6 months old or younger to have RB1+/+MYCNA retinoblastoma is 20%; the younger the baby, the more likely they are to have this form of Retinoblastoma.

Among the children with MYCNA retinoblastoma in the study, none developed new cancer after prompt removal of the unilateral affected eye, but they all had large aggressive tumours, including invasion into the optic nerve.

Since identifying RB1+/+MYCNA retinoblastoma, doctors in the research team have identified children from clinical features alone as being at high risk, subsequently confirming their clinical diagnosis with pathology and genetic testing after enucleation.

Though the number of children with this form of Rb is very small, recognizing the risk is important in clinical care.

Doctors widely accept that a young baby with unilateral retinoblastoma will have a constitutional RB1 mutation, posing a threat to the other eye. This prompts greater effort to save the affected eye. MYCNA tumours grow and metastasise very rapidly. As children with this form of retinoblastoma usually have advanced cancer at diagnosis, attempting to save such an eye may be highly dangerous to the life of the baby.

MYCNA retinoblastoma is not heritable, meaning the patient’s other eye is not at risk, other children in the family do not need to be screened, and there will be no risk to the patient’s children.

Lucy endured seven months of treatment in attempts to save her eye, and a further 7 months of treatment to save her life. This sustained aggressive treatment could have been avoided with early enucleation, had her doctors been able to identify her risk for MYCNA retinoblastoma. This new discovery will help spare other children this unnecessary and life-threatening trauma.

More research is needed to better understand the genetic changes that cause and drive development of MYCNA retinoblastoma. These tumours show features of neuroblastoma, and research is needed to establish whether neuroblastoma protocols have value in treating babies whose cancer has already spread at diagnosis or relapses after enucleation.

The researchers also found no explanation for the cause of retinoblastoma in half of identified RB1+/+ tumours (1.3% of the 1068 tumours studied). Further research is needed to determine the cause of cancer in these children.

This is a significant advance in retinoblastoma genetics that has immediate impact on life saving clinical care. The study also shows how international collaborative research can overcome barriers of rarity to find answers rapidly that have immense value in guiding quality care of patients and their families.

Read more about retinoblastoma genetics in our Rb Resource – 300 pages of practical information and tips for families, survivors and communities caring for someone affected by retinoblastoma.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!